Technology is both my best friend and enemy. In the mornings, my practice has been to open my email and start the day by knocking out to-do lists before I write. The writing never comes because the lists are always so long.

Then something happened the other day.

I was in my usual state of avoidance. Paperwork was strewn about, and my mood set to blame someone for my writing blocks, which were firmly established. And off I dove into the rabbit hole of the internet.

But somehow, I struck inspiration. I clicked on The Washington Post’s Optimist newsletter and saw the headline How memorizing poetry can expand your life.

Intrigued by two subjects feeding my fear of failure – memory and writing – I had only one choice but to click again.

I found myself reading and rereading Jacob Brogan’s piece. On a cursory level, what would appear to be a well-written tale of his rediscovery of poetry brought me so much more- a sense of relief of blocks to writing, living, and Grace. It may have been his intent, perhaps not, but his story and its links led me down more and more tunnels and funnels of the World Wide Web. As I burrowed my way through reading back stories of the Polish Poet Adam Zagajewski and writer Leslie Hazelton and rekindling my love of poet Ann Sexton’s confessional content, I discovered bits of myself in the journey.

I found solace in the stories in a way I had not found comfort. And though these words were transmitted through the ether to my desktop, it felt as though stacks of books were landing before me, pages unfurling to reveal the perfect words that stirred in me focused thoughts and images. The stories and articles that followed and flowed felt like a fantastic tacking maneuver, wind blowing across my bow. I was immediately sailing into the words and carried off.

It’s been a long time since I felt this way—or perhaps a long time since I acted on the feeling. It was always an excuse to shy away from the work. That word work, it would seem, is what the block was all about—not that the work was daunting, but the word.

We have all become so accustomed to equating our worthiness to work. How could I be a writer if I had abandoned my craft so many years ago to create our businesses with my partner? What right did I have to consider myself a writer if I wasn’t earning a substantial living from my craft? How braggadocious to provide me with a monicker to which I was so profoundly unworthy.

Brogan’s story led me to Devin Kelly’s Ordinary Plots article on Adam Zagajewski’s Transformation. Kelly’s take on the poem had this little subheadline: “Thoughts on not writing.” I was hooked.

Aside from the grateful reminder of the book The Raft is Not the Shore, which I can’t wait to rediscover, Kelly reminded me of the burning drive I held in my early 20s and even 30s to write. And I wrote with a prolific fervor. It made me smile that his newly 30-year-old self longed for the passion of his younger years. He tossed about some beautifully reflective thoughts that seemed to heal some parts of this (dare I say) nearly 60-year-old woman’s artistic soul. His youthful wisdom made quite an impression. But more than that, he commented on the challenge of being a writer and balancing that title with the age-old American societal question of “what do you do?”

Writers are artists. Although most of us cringe at the title. In a society that places so much importance on money, success, and fame, the artist’s path is rarely filled with or paved with much of it.

He writes, “The problem with associating art with some kind of economic idea of work. As in: if you don’t produce, you are failing in your labor. And then, if and when you do produce, you begin to — consciously or unconsciously — attach all of these ideas to your work. These notions of what success — a purely economic term — must look like or feel like. And how you might feel bad for such notions, but how you might need to really consider them because you might need to be supported for your art, which is now also a kind of economic work, which is now necessary for you to live. Do you see how complicated it can get? How painful, perhaps, to try to produce art in this world when you really just want to create it? “

He continues, “In moments like these, when the work feels distant and the world feels ever-present in all of its often weird and often oppressive and often beautiful and often strange and often terrifying ways, I try to remind myself of Grace. It’s a reminder that has its difficult days and its easier ones… I try to offer myself Grace for the work of being alive. It’s a kind of work that manifests itself differently for each of us, but it is work for each of us nonetheless. I try to offer myself Grace, because I believe that if there is not compassion — for the self, for others — at the center of this wild and messy thing, then there is a void at the center, and that void will be filled with something other than Grace, but something regardless, and maybe something worse. I’d rather choose Grace, even when it’s hard.”

This reflection sprouted from Kelly’s dissection of Zagajewski’s poem, and his reflection on the material helped transform me. For the first time in eons, I felt hope rather than angst or jealousy of this young man’s commitment to the written word, which I have felt abandoned me. I looked toward Grace and discovered what had always appeared as a window that brought Grace to the world; today, it was a mirror reflecting Grace at me.

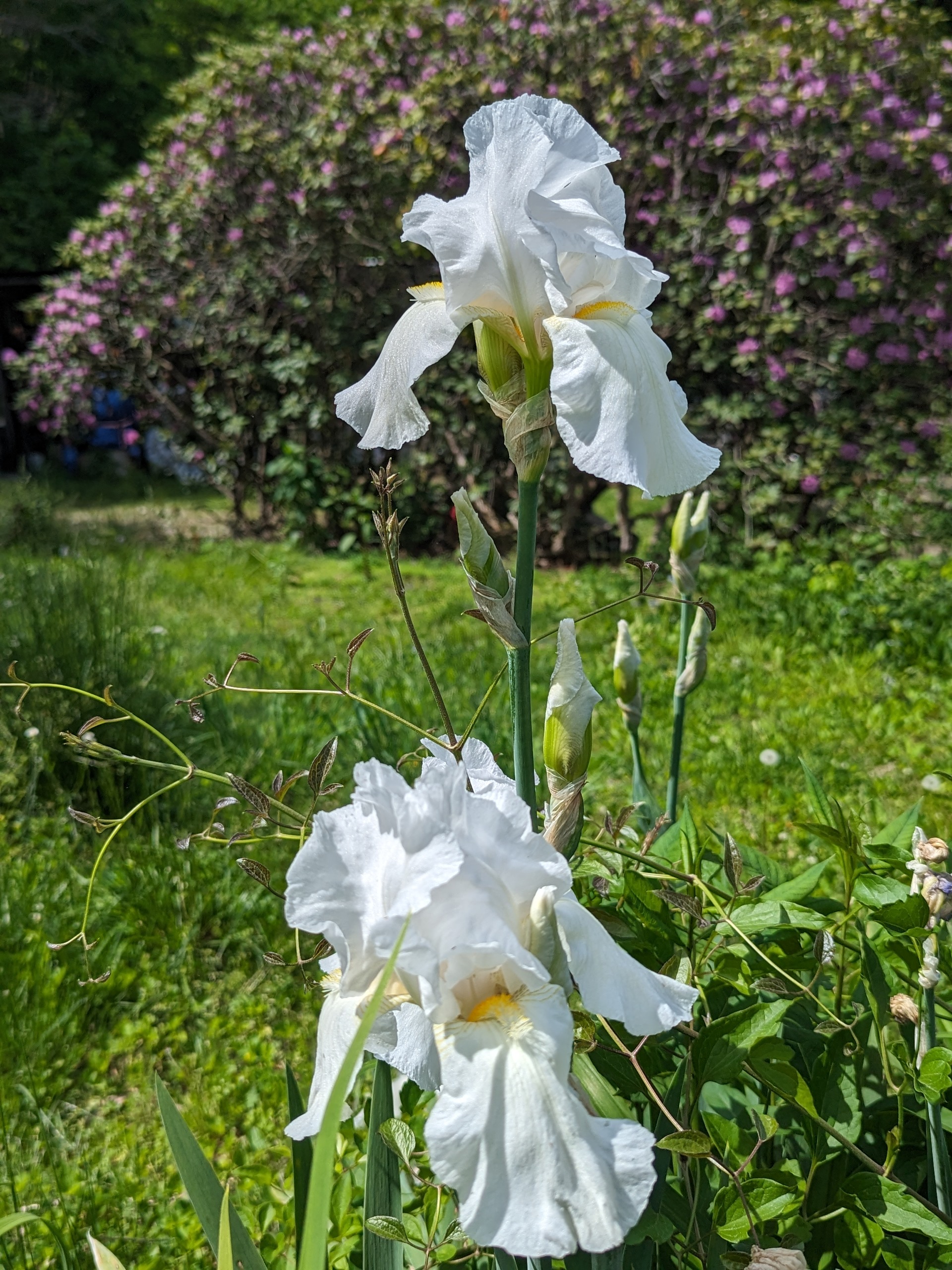

My approach and thoughts of writing shifted like the wind heeling my craft, and I caught speed. Kelly referenced another writer, David Searcy, who, in his book The Tiny Bee That Hovers at the Center of the World, writes this line for one of his characters: “Start with a beautiful thing, then bring the angels to it.”

Kelly writes, “That final sentence — I will think about it for a long time. Start with a beautiful thing, then bring the angels to it. I want to think of that not as a way to define the act of creating art, but as a way to define the act of life itself. Start with a beautiful thing, then bring the angels to it ….[But] I also think of that word — transformation — and how it means not necessarily to change one’s likeness, but more so to move across and through and beyond an idea. This, I think, requires Grace. The Grace to say it is okay. The Grace to say the way I am an artist today does not have to be the same as yesterday. The Grace to say I am starting today with a beautiful thing. I want to move to that kind of permissiveness with myself and my art. I want to allow myself stillness, to remove expectations that feel stifling, borrowed from oppressive structures. I want to permit myself to simply notice. Not everything turns into song. Maybe that, too, is a kind of song. And maybe, just maybe, when the angels come, I won’t be too caught up in myself to see them.’

So, I will continue to show up at the keyboard each day but lay those expectations of the world at my office door. I’ll invite Grace to sit beside me and check the direction of the wind. I will look for something beautiful and begin painting with words.

And hopefully, I will catch a glimpse of an angel in the process.